From Map Making to World Building

Turning up the complexity as geospatial evolves

Cultures the world over have a creation story. Some of these stories tell how the world came to be, some tell of the animals, and some tell of humanity’s emergence. There are several categories that creation stories cluster into: creation from chaos, creation from a void, emergence, the earth diver or seeding, birth by divine parents.

I recently visited Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, a historic Maya region where crumbling stone structures—pyramids, palaces, houses, monuments—give echoes of a world both forgotten and destroyed. Maps like OpenStreetMap show the layout of the ruins in places like Mayapan, Chichen Itza, and Uxmal. Men in sun hats shout offers of guided tours, while booklets in the gift shop give a concise written version of the history and significance of each fragment of the past.

To recreate this world often takes a stretch of imagination, envisioning what it once was, as well as the careful work of experts who have pieced together a past where memories were stolen, where records were burned, shipped away, or lost. The Mayan world—its architecture, but much more as well—exists in a time and space we can’t entirely see in the real world, but might visit through art, science, storytelling, and visualizations.

The Popol Vuh, a text from one of the Mayan cultures, tells a story of gods in the cosmos coming together to build the earth then populate it with humans. In Genesis—from the Greek word for origin or creation—the orderly world is created from chaos in six days, layer by layer. The Norse Völuspá describes the gods pulling the earth from the sea, while the Navajo Diné Bahaneʼ tells of multiple intangible and underground worlds through which humans pass before emerging into the fourth and present world.

In these myriad stories, a world is built. The methods vary, as do the materials, the influences, the inputs, the motives. Yet the intention is clear: to communicate how things came to be the way they are, particularly how the physical environment and the life which inhabits it came to exist. Whole civilizations created their own cities, forged their human footprint, and yet also had to create their own story to suppose how it all came about with the distant origins of such world building being a faded and lost memory.

Today the geospatial and mapping industry is writing the creation story of the next generation of maps. Everything to date has been designed to act and feel like paper maps, but the future of maps demands not just a map surface but an invisible world to be built which mirrors and reflects the landscapes we inhabit. This creation is not yet here, but constantly in progress.

Questions remain about the category this creation story will fit within. Will it be order from chaos? Does the digital world emerge from the physical? Do great thinkers, engineers, and designers give birth to the new ideas behind the future maps? Is it something else entirely?

Worldbuilder

You will notice that this publication has adapted its name to a new theme: Worldbuilder. Going forward, the subject matter will not change greatly from before, with a focus on geospatial topics, designing the future of maps, exploring how people use map products, and considering deeper cultural meaning within these, beyond the business and the technology. The name reinforces this, emphasizing the idea of not just making maps but building worlds that are rooted in reality.

World building is not map making, although it grows out of it, depends upon it, and thrives with it. While air travel is map making, space travel is world building. World building means not just indexing things—giving them a place on the sphere and attributes—but also recreating the dynamic physics engines around those things.

World building also means data collection in a way that is not so much like an artist drawing an impression, but like a photographer, a videographer, capturing reality in a specific moment (quite literally). World building means making imprints, copy-pasting reality, and hence re-building the real world.

Map Making

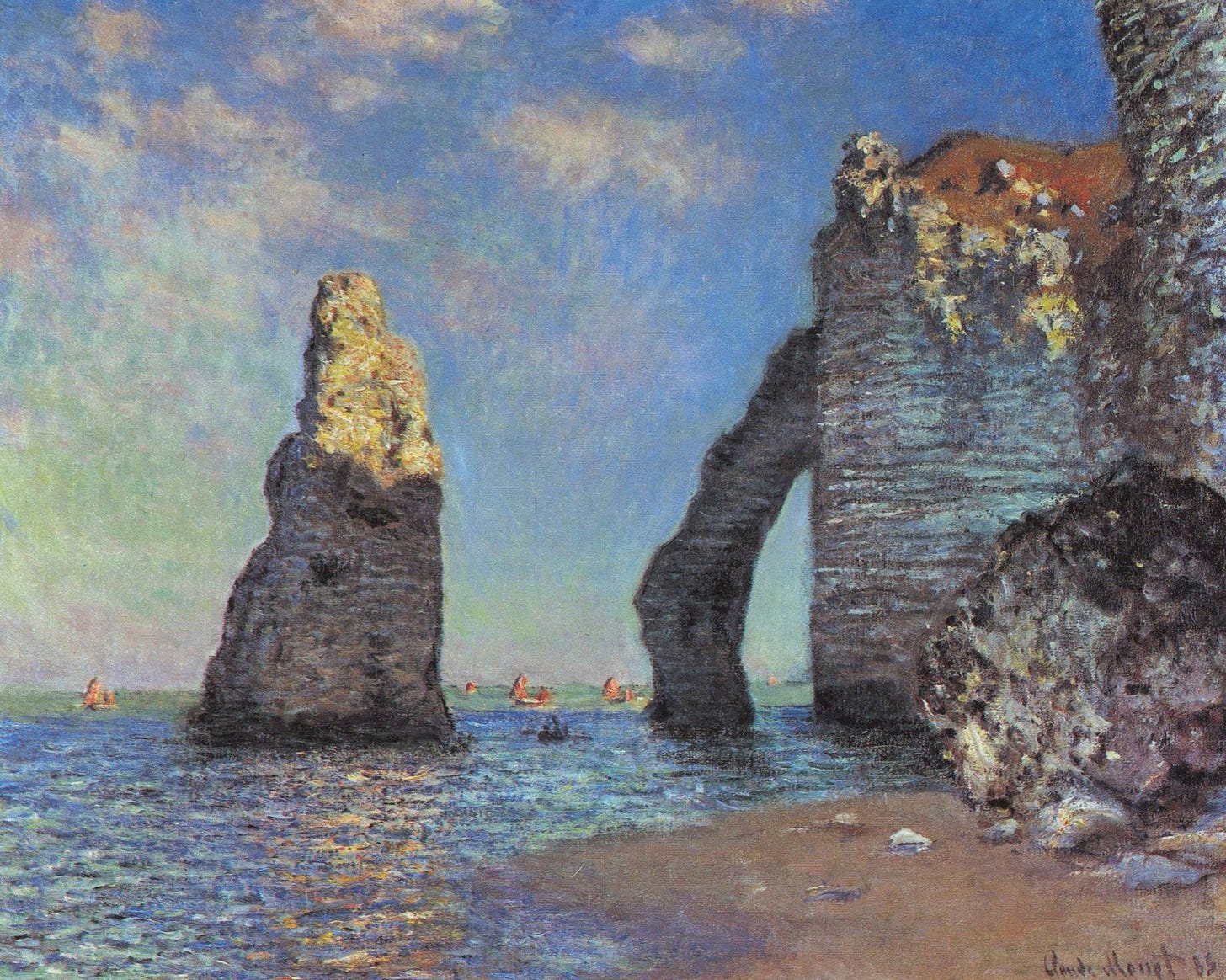

Maps are easily and poetically said to be related to the real world in so many ways. A reflection, a copy, and an index. A twin, a simplification, a lie, a snapshot. A symbolic model, a network and graph, a representation but always wrong. A map is like Pablo Picasso’s lie (translated from Spanish):

We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.

Map construction is an art and science of data visualization, of cartographic design. Map making is the work of many hands to produce these map surfaces that proliferate across our devices, print on paper, display on screens, and rest in our minds. Adjacent to maps we have geometric problem solving and human-machine interaction study.

There is map making, and then there is world building. World building is something bigger, and deserves careful consideration of what makes it different from, yet an extension of, map making.

Middle Earth Building

A few years ago I typed “world building” into a search engine, and the results were dominated by links to table top roleplaying websites and video game forums. Some results also point to fiction writing resources.

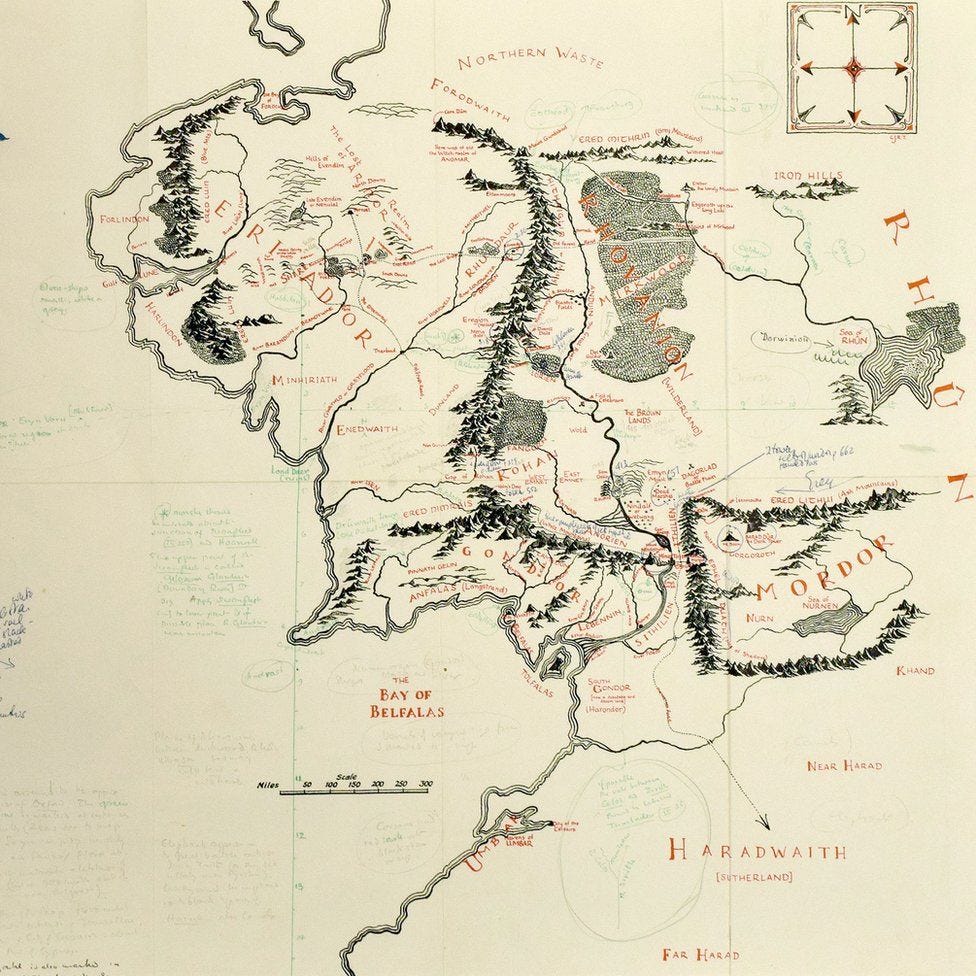

Lord of the Rings is one of the most interesting examples of this definition of world building, but in a way that begins to relate to the future of world building as I will describe it.

Perhaps you know the place called Middle Earth? Perhaps in some sense, you have been there? JRR Tolkien created this world, referencing many geographical elements of the real world when conceiving its geography, and also borrow from existing human cultures when devising languages, politics, and peoples of the lands he sketched. Without any further explanation, this concept defines world building.

Decades upon decades later, a video game called Lord of the Rings Online, or LOTRO, was created. I remember in my younger days spending hours and hours playing this game, being particularly mesmerized by the visual beauty of the 3D animated world of the game, bringing both the books and the movies to life in an imitation of the real world. Lakes, forests, glowing sunsets, vast landscapes, bustling villages, wildlife and open sky—all these made this fantasy world first devised in a map and written word into something I felt immersed within.

In this video game, using powerful graphics engines and thanks to spending too much on a nice graphics card and extra memory, I was able to see a world built in a less literary and psychological sense, but more a physical or spatial sense. Older video games also build entire worlds, both spatially and in their lore—the Legend of Zelda, Super Mario, Grand Theft Auto, Age of Empires, and many more. Meanwhile, games like Flight Simulator begin to use world building in the sense of actually modelling the real world as the environment one flies through and within.

Many maps in our modern civilizations began like Tolkien’s world building, representing a mental model of space in writing and sketches. Cartography later evolved to be more precise, blending into the world of geometry. Mathematics, trigonometry, measuring not only distances but arcs and angles became essential to a geographer or cartographer. Places became stored in tables, pencil sketched lines became encoded data, and the map cloned into a database, a geographic information system.

Mapmaking as a way of modeling the world’s things for the purpose of understanding it has already long ago given way to world building, as a way of reconstructing the world, building it anew, modeling not just its layout but the atmospheric and environmental aspects, such that the lighting in a 3d model is realistic based on latitude, date, and time.

Buzzing words

This professional concept of world building is perhaps called making an HD map, or a digital twin, or 3D maps. The word metaverse bounces around with some more cosmic relation to the idea of maps and a model of the world. Augmented reality is heavily reliant on a model of the world that needs to be built, as recent announcements by Google tout the importance of Google Maps and Street View in making AR work globally. Google, among others, is not just mapping, but is building a world, making a digital twin, making self-healing maps in HD, ensuring that the real world has a parallel one in the cloud.

World building is less of a common buzzword, if one at all. But it is an apt term to umbrella many of these practices that go beyond just mapping and mapmaking, and will come to define the function of many tools, methods, and teams in the geospatial industry as it pursues new horizons.

The new world

World building is not a sudden transition from the geospatial methods of the past, but in my view a gradual transition that is becoming more and more apparent. It deserves more explicit coverage, and serves to zoom out and zoom in at the same time: see the more microscopic and macroscopic aspects that connect maps with futuristic ideas that depend on maps. While mapping often distills and simplifies the world, at best in closed systems, world building will seek to model the open, complex system of reality and it’s many variables—and I look forward to follow its emergence here on Worldbuilder.