The Immersive Map

Making the world into our canvas

“There is no need to build a labyrinth when the entire universe is one.”

— Jorge Luis Borges

Our idea of a map is deeply rooted in history: it is visual, it is Cartesian, everything has an x coordinate and a y coordinate, and sometimes a z coordinate. It comes from the paper map, just a digitized version. We have Pacman-like perspectives of space, which we improve by aiming to take out maps from Super Nintendo's graphics to Nintendo 64, with the 3d maps touted as a realization akin to a Flatlander encountering the third dimension.

As map consumers we also have the eyes of birds, looking down on the earth from far above. We can zoom, we can pan, we can search for anything, anywhere. When satellite and aerial imagery are not enough to complement the vector maps, we have places photos, street view, even LiDAR and 3d models assembled using photogrammetry and structure from motion.

We have the ability to model the world. We have the ability to index the world. We can build a replica of a city in 3d graphics, and label every object and surface. This is powerful for purposes such as asset management, VR entertainment, machine readable maps for an autonomous vehicle. But what does it mean for consumer maps?

“The world will be painted with data,” said Charlie Fink. Modeling the world means taking a copy of it, using it as a canvas in a test environment, learning how to paint data upon it, then draping that data back over the real world by modeling it in real time--or referencing the real world against the model on the fly.

A robot can use a digital twin of the earth like a train uses rails. Loaded with cameras, it can analyze everything it sees building a real time 3d model, perhaps using Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM). It can compare the imprint of the world that it makes, and its relative location within the imprint, to the 3d map stored in it's memory.

This is much like a human walking through a shopping mall, perhaps a little lost, but remembering the previous visit and constantly comparing reality to memory: “Ah right, the last time I was here, I stood by the fountain, and the chocolate shop was next to the Starbucks, so I can turn here to find it.”

A key difference is that the human is referring to actual learned memory. In another situation they may open a paper map of the mall, or open an app on their phone to glance at. The robot is using a “memory” implanted within it, but essentially the same as the mobile app, just more immersive: the robot has access to perhaps a comprehensive model of the world, albeit a month or a year old, that it can reference to mostly understand what it sees today.

Looking up or looking around?

A goal in the mapping world seems to be to create that comprehensive model of the world, using even more detail, and present it not to the robot but to the human.

If I am walking through an urban park and finish drinking my delicious honeydew flavored bubble tea, where can I toss the container? If I am desperate, maybe I check a map. Do I need a perfect 3d model of the park to search “trash bin” and find the location? This seems like overkill on my phone.

A robot might do exactly this, and just set a route to the trash bin. As a human, even if that model was available, I would likely not bother in this situation. I would just look around for a trash bin. It happens often, and I am not bothered by the fact that it could be ten minutes until I come across one. I probably won't go off my route--maybe on my way back home at this point--just to find the trash bin.

In fact, finding these small things is a bit of exploratory fun. I don't really want to be so efficient that I always know where to find the nearest trash bin, bench, or shady tree to sit beneath. But if I urgently need to use the toilet, you can bet I probably want to immediately know where it is and be directed that way rather than spend 10 minutes “exploring”. There is a balance.

Future maps should not be oriented around over-optimizing our spatial life. If we stop using our eyes, the random encounters of aimless walks, or route finding by simply taking a guess and adjusting as we go, then we start to live in our phones, live in the map, and we find out eventually that we are unhappy with a life devoid of spontaneity.

Immersion but not invasion

The next maps will be immersive, not in order to suck us into their world, but in order to inhabit our world.

It may very well be augmented reality. But if you are like me, you probably see wearing glasses, even contact lenses, or some other device as a barrier between you and the natural world. Personally, I just don't need it. I don't have a problem that needs solving with a device on my face.

At least, not in everyday life. But in certain situations, I do want a tool that makes the experience more practical.

Enter the Skier

One of my favorite hobbies is skiing. Resort skiing, speeding down hills. Moguls, finding creative routed through a forest, rushing down steeps. Backcountry ski touring, hours going uphill, sun on the face or blizzard in the beard. It's an amazing way to connect with nature, yet I use all sorts of tools to improve the experience.

When I ski, I have of course the skis themselves, and they are far more advanced than the wooden boards on the feet that the pioneers of skiing used. Even in the Altai Mountains and Mongolia, locals were putting mohair or elk hide on the undersides to allow a grip for uphill travel. I now have sticky skins I can attach to my skis to go uphill, and pack away when going down. The shapes of modern skis are very calculated, to ensure turning, floating on powder, and other actions are optimal. I have a Garmin InReach with an SOS button for the hopefully once in a lifetime moment of danger. I wear an avalanche beacon that helps locate me under a rubble of snow slide, or that pings others letting me find them if buried too. I have a helmet, clothing for different temps, tools to maintain and adjust my skis. And I have my goggles, with polarized lenses, helping me see in the bright sun and glinting white landscape, and probably with some design to avoid fogging up as I radiate heat and sweat.

One extra tool would revolutionize this experience. It probably exists. I would love to work on the software design of it. It is highly geospatial in nature alongside a hardware and UX challenge. This is the idea of an immersive, yet minimalist spatial ski goggle.

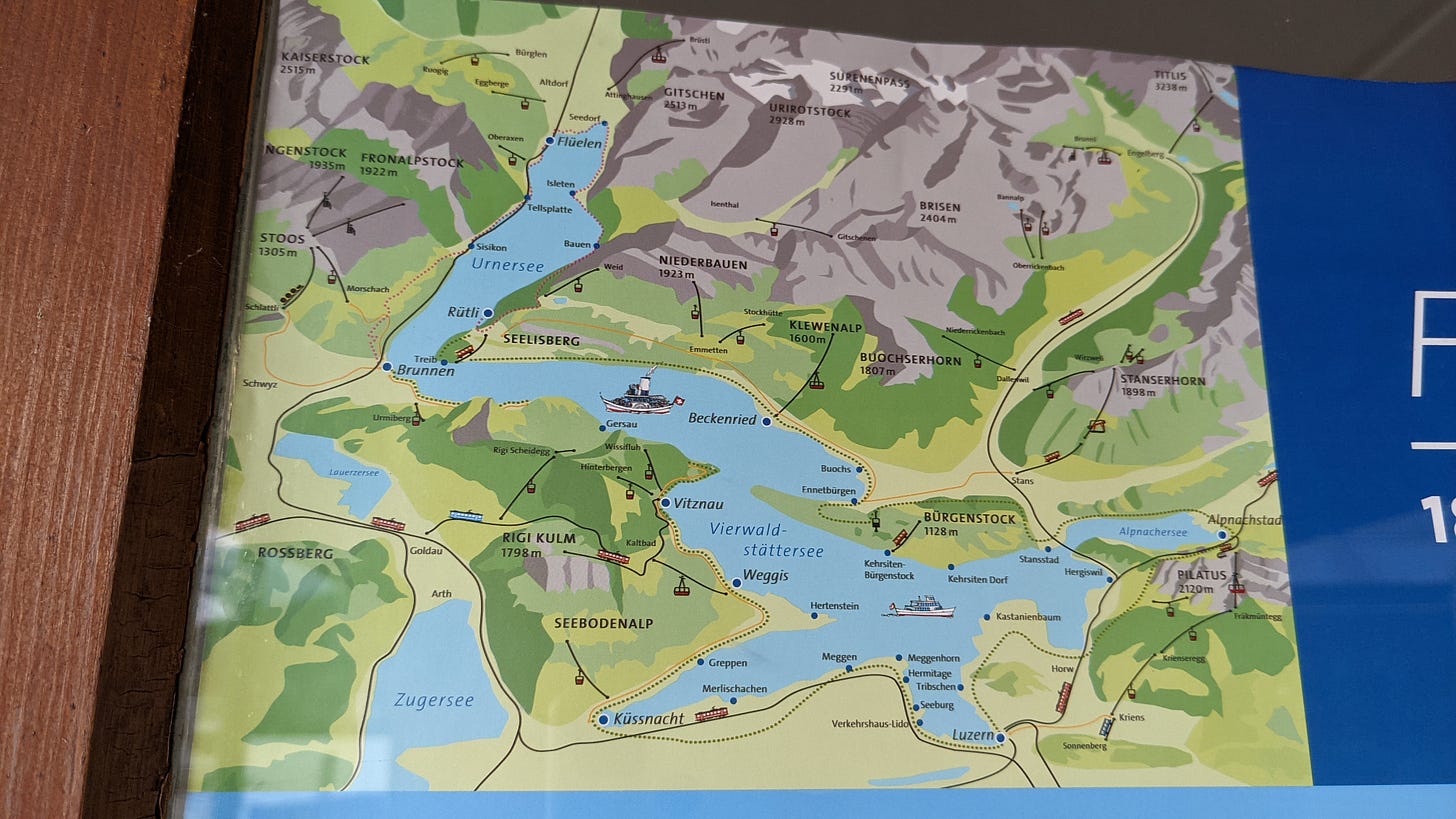

Imagine it, even beyond skiing: you are with friends in the mountains or wild lands. At times you become separated. Like a video game, an arrow indicator subtly says that friend A is 205m in one direction, and friend B is 322 meters the other way. You are heading to a bridge somewhere ahead, and an arrow points the way. On skis, you can start moving quite fast, so you speed can be visible. You could change the route, selecting a mountain hut as the destination, and it recalculates. If someone was injured nearby last week, a virtual marker may be dropped at the location as a lasting warning to others. The land to the east may be a protected nature reserve that you should not enter, so as you near it a warning rises, and the boundary line shows in your vision (all this is very Swiss oriented, and of course the world is more than snowy mountains with huts dotting the horizon: so imagine another scenario if you can).

If immersive but not intrusive, I would be thrilled to use this (shoot me a note if you're already working on it!). It would make skiing a bit safer, a bit more fun, yet would not turn the experience in nature into something tainted by technology.

I don't want this tool for visiting a park. Nor sitting in my home. Nor while at a restaurant, or while writing or reading a book. Yet I do have my mobile phone handy, or often have my eyes on it, in these situations, so subconsciously I am not strictly dividing my attention away from technological augmentation in these situations. So perhaps there will be a slowly expanding sphere of use for such a tool, from my ski goggles to my sunglasses.

The unseen world

Google Maps has an augmented reality style navigation experience. It is not truly augmented reality, in that the user is immersed. In my view, nothing is AR when glanced at through the phone, thus is just augmented pseudo-reality.

It is not a revolutionary feature, but points toward the future. There is a great advantage to being able to navigate a labyrinthine city without constantly staring at the phone, or pausing at each corner to glance at a map. One way of avoiding this is to not navigate at all, but simply to wander.

Life does not always work this way, however. We sometimes, often really, need to get where we are going. In days far behind us we may have relied entirely on signs. We still can really: many roads tell us where to turn based on our destination, while town streets and walking paths sometimes have signs saying which way to the post office or the train station or the museum.

Google's AR navigation creates these signs in real time: sometimes it is just an arrow, pointing toward the destination the user inputs. It also can add markers in the camera view indicating the name of POIs in the distance, making it easy to see through walls and city blocks when wanting to add a spontaneous detour.

Yet the whole time your chin is down, looking into the phone, or your arm extended, holding the phone to your eyes. It's not ideal, and we all know it. It is a deal breaker, really.

To be immersed in a 3d world model, we also want to not see the model. We want to see the real world, but be able to search it, to receive cues and information about it. It is not just a “hands-free”, but an “eyes-free” scenario.

Labyrinth of Labyrinths

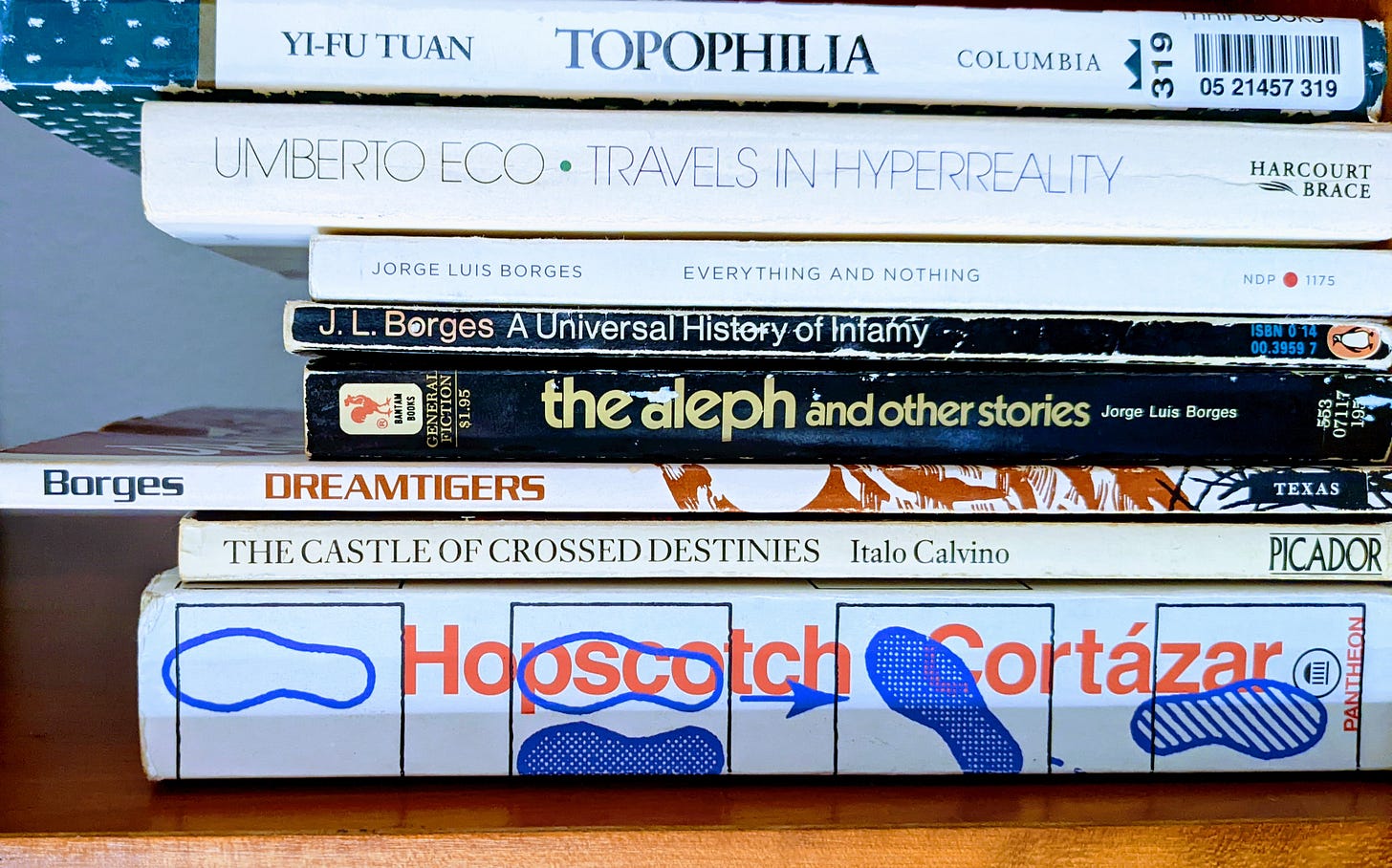

I would guess many an article, when talking about HD maps, digital twins, 3d models of the earth, and so on have quoted Jorge Luis Borges. Specifically, a single paragraph short story about a map of the empire, that reaches a 1:1 scale and is later forgotten. This is nice, but misses the mark on both the future of maps and on Borges' ability to inform us. The future map is not 1:1, nor needs to be, but it has some wacky puzzles about time, space, alternative paths, and unknowable aspects that our technology and minds have yet to solve.

I have read almost everything Borges has written, from takes of back alley knife fights to praise of eternal libraries to strange other worlds to labyrinthine views of consciousness. He was no cartographer nor technologist, and in fact was quite blind by the time he died of cancer in Geneva. He does not provide us a model for the future, nor a prophecy, but inspiration perhaps.

Consider a spatial view of the world in our minds and computers, the concept of a map, like Borges describes a book being:

“A book is more than a verbal structure or series of verbal structures; it is the dialogue it establishes with its reader and the intonation it imposes upon his voice and the changing and durable images it leaves in his memory. A book is not an isolated being: it is a relationship, an axis of innumerable relationships.”

Consider how maps reflect what we need and want to see, and sometimes distort reality to serve our needs or views:

“A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.”

Consider the constantly changing world that maps must adapt and heal to reflect as if they are a stable truth:

“Nothing is built on stone; All is built on sand, but we must build as if the sand were stone.”

On mixed reality, a map of the world or the world of the map, our human eyes and brain looking at the phone and getting back spatial information about the world around us:

“It only takes two facing mirrors to build a labyrinth.”

There are many more gems, but I recommend to read his stories. The Aleph is perhaps the best one that could make us think about the idea of trying to make a copy of reality that we reference, or The Library of Babel to consider the complexity and convolution of information systems. All of it has some relevance to the puzzle of aggregating spatial knowledge of the whole world, and serving it out to anyone, anywhere, as their own knowledge.

We are the map

Probably the biggest challenge of future mapping is that it is a constant labor to take a snapshot of the world and index it. The world is constantly changing, but even if so, it is too big, in a fractal sense, to turn into a comprehensive map without an enormous decentralized method of mapping.

Games like Pokemon Go attempt to decentralize the data collection. Communities like OpenStreetMap also do it. Mapillary, OpenAerialMap, Flickr, Foursquare, and many others all look to aggregate data from many individuals.

A vision of a future map is something like an ant colony where a hive mind uses the many drones as sensors. This is already happening, with mobile phones in most of our pockets, and nonhuman things increasingly connected and acting as sensors as well. We monitor the world from above, from within, sensors sensing one another even. But it still is not enough.

There are many versions of reality. Borges tells a story of a knife fight, and later retells it from scratch, with details different. It becomes clear that he intends this to show the relativity of human perspective. One observer has their version, another a different one. The same issue arises with map data, for example points of interest (POIs) having different attributes based on who provides the data and when. Precise measurements can vary and evolve, while subjective things never have a foundation to vary from.

The perfect future map is a machinated version of local knowledge. Have you ever known a place so well that you could navigate it, give advice, notice slight changes, all without a need for a map or an app? Notice in a city, whether it is Zürich or Zacatecas or Zanzibar, there are people moving about deliberately, without use of a device to navigate. The map is in their mind. Some have had it mapped for days during their brief touristic or business visit, some for decades of growing up down the street.

Local Knowledge and Localization

There are places where local children know a passage, under a bridge or through a forest. Shortcuts, scenic routes, low traffic detours. There are places where even Google Maps or OpenStreetMap will not be too helpful, because the streets are such a maze. This is especially true in a pedestrian area, where the brain struggles to match the 2d map to the visual world around it--it is a constant conversion between a geometry language and a sensory one, where things get lost in between.

Bring a visitor to a small city like Locarno in Switzerland, and they will likely know their way around naturally after a tour guide shows them around over the course of a few days. The mind maps, the mind learns.

Then go to a bigger city like Miami, and it may take months, even years depending how far from the center one goes. The mind makes a micromap of the places they spend most of their time, and a macromap of something like the transit system, highway, or which neighborhood is where.

Software aims to achieve a similar understanding in meeting the needs of a user for a consumer maps app. It is not just a catalog of places, an index of things, a network of routes. It is highly psychological, behavioral, contextual, and selective. Artificial intelligence seeks to mimic sentient learning and behavior, while artificial and immersive maps need to similarly mimic how people perceive space and analyze it--then augment human capability by presenting more reference data than we could remember or learn independently.

Augmenting our spatial reality

There is a difference between augmented reality and AR maps. AR on its own, in my view, will be most useful for practical purposes. This includes factory work, or being in a platinum mine, military operations (night vision is quite like an AR/VR experience—I once did a nighttime training opération from a Black Hawk, landing the chopper in a field where we jumped out wearing infrared and clumsily tried to scramble for the treeline and secure a perimeter).

There is a spatial component to much of it. But say we somehow get past the hurdles of AR adoption—if we even decide collectively, even as a niche community, that we want to and it is good for us. At that point, what will a mapping app installed on your AR hardware/operating system look like? How do the components I wrote about in Unbundling Google Maps get adapted to be part of an immersive experience?

There are two approaches needed to make truly immersive and intuitive maps. First is the creative component, which is to determine how the human interacts with the complex system of mapping. The other is a logistical problem of scale, and that is how to collect or generate all the needed data.

Mostly, the future is already here: in the backend, under the hood, unseen by the consumer. It is the user interface and user experience that is yet to be determined. It is how the backend delivers the service, in a novel way that is not a mobile phone screen, that is the open question.

Fundamentally, the highest utility future map is one that augments our knowledge of the world, but most specifically does so in the innate way that we look at Locarno and Miami: it gives us hyperlocal knowledge about places nearby, even in a 20 meter radius, while also giving us context about how the local scene fits into a larger environment. And all this without removing us from the flow of daily life and going into a parallel world (a metaverse, a phone screen). We stay here instead of going there.

At this moment, I do not know where the closest art supply shop is. I need to open my phone and search. I do not know the walking route from a hotel in central Boston to a park in Cambridge, across the river--I don't know the location or name of a bridge to take, and not even slightly what the route is, because I've never been to those places ever. Google Maps could tell me, but I won’t truly know until I experience it.

Possibility and Paradox

The next generation of maps will not be the typical visual, surface based reference. It will be intangible. It will answer the age-old questions of where, and how to get there, and what is around, and which to choose, but by giving us the sense that one moment we don't know, and in the next moment we know it.

Augmented reality can achieve this immersion, a mimicking of actually having spatial knowledge out of thin air, but the problem is how to be informative and not invasive. Glasses and visual aids may be too awkward and conspicuous. Perhaps sound can help. Perhaps something neural, or perhaps there will never be anything better than the real thing: the natural process of human learning that gives us a sense of place.

A final word from Borges to summarize the situation:

“The man who acquires an encyclopedia does not thereby acquire every line, every paragraph, every page, and every illustration; he acquires the possibility of becoming familiar with one and another of those things.”

The future is unwritten—unmapped—but we know what we are seeking, and that is an independence from technology as a distraction, yet an immersion in the data and capabilities that technology can deliver to us. It is a paradox, and a world of possibility bounded by practicality.