Toponymy in Mapping

The past, present, and future of place names

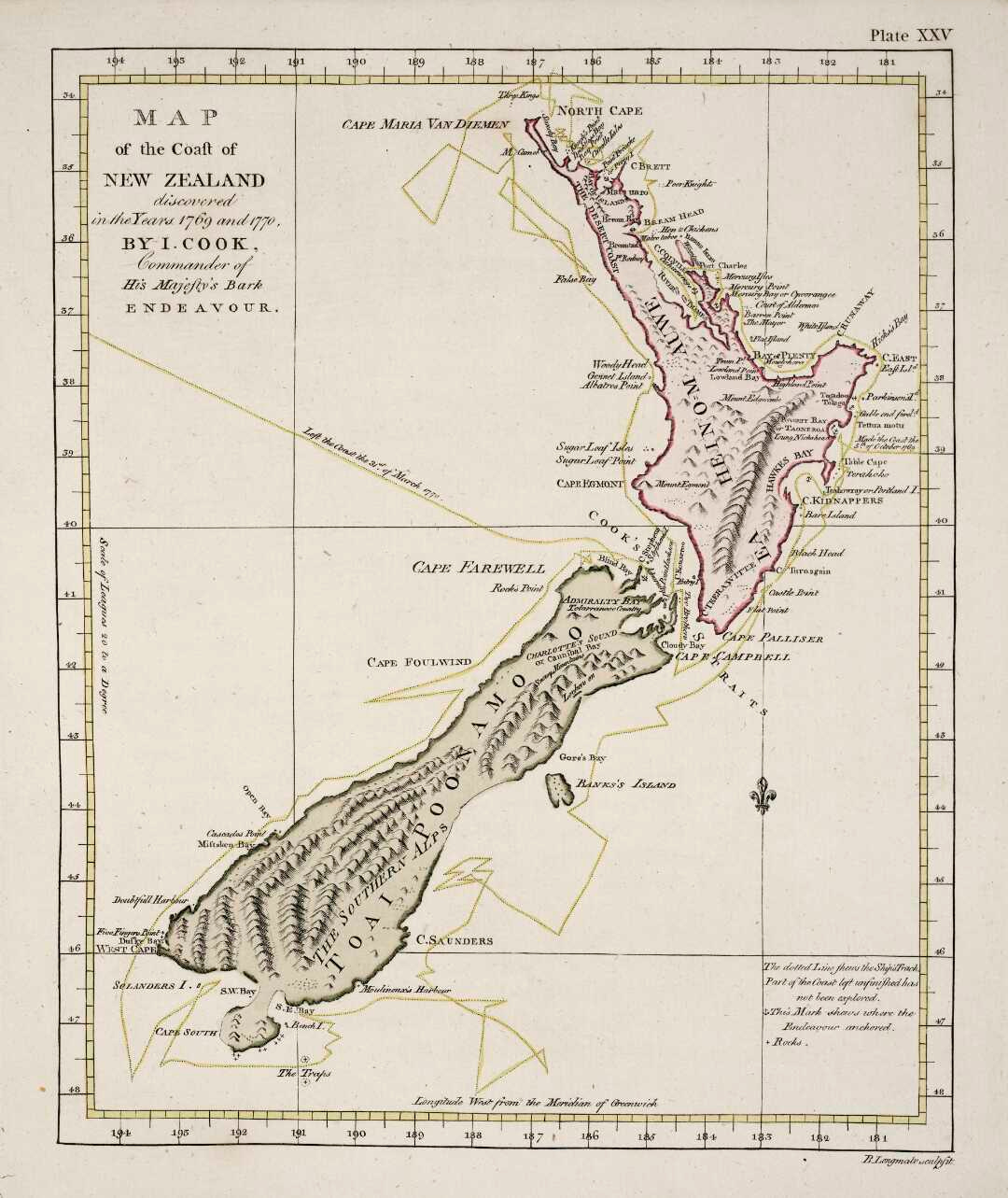

Place names became very interesting to me years ago as I followed various debates about the naming and renaming of places according to different histories and languages. When I visited New Zealand in 2019, it was very noticeable that locals often referred to the territory itself as Aotearoa, rather than using the European name that is derived from Sjælland in Denmark. To me this was hardly controversial, though more historical tension is visible when talking about more granular places—point data, rather than big polygons. Mount Cook, with its national park, is known also as Aoraki, and officially uses both names. An interesting note is also what the names mean—Aoraki being the name of a spiritual Polynesian figure, Cook being the British Navy captain who explored much of the Pacific.

Many places are named after people, whether these are mythological, historical, political, scientific, or have some other category of significance. I recently began reading an environmental history of the Alps by John Mathieu, and an early part of the book notes that something like 20% of places in Savoy—the Alpine region where France and Italy meet—are named for Christian saints.

While many parts of the world that experienced colonialism often have a controversy over names—whether this is from English, French, Portuguese, Arab, or Ottoman Turkish influence, for example—many other parts of the world find the idea of multiple toponyms to be quite natural. In my home state of Montana, many of the names are in English, but are transliterations of the local Crow language, among others. In Alaska, Mount McKinley—named for the assassinated president of the early 1900s—has reverted back to Denali, “the tall one” in a local Athabascan dialect. Teotihuacan (“city of the gods”) in central Mexico is a ruin that retains its name, but no one knows what language its builder spoke or what they called it. Mexico City embraces the name of the Mexica, the Aztec inhabitants who arrived in the 1200s, while their city Tenochtitlán ("among the prickly pears of the rock”, referenced in the Mexican flag) has vanished in place and name, except a few ruins and infrastructure remnants. In many of these cases there is at least some agreement that places must have a particularly official name.

On a paper map, single official names are often required, at least as a design choice. These can, however, become long lasting cultural and political choices too. Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps on the French and Italian border (Monte Bianco in Italian), was known by other names only a few hundred years ago, by the same inhabitants. Maudit Montagne was supposedly the most common—“damned mountain”. By the 1800s, Mont Blanc was the name that maps carried, as maps themselves became less fluid and decentralized, and more of an institution representing the geography of a nation, its international treaties, and the dogma of its place names.

For the Alps, this entire era of the early to mid-1800s became a time where place names assumed a more final, lasting form, turning local vernacular into archived, often more formalized and rewritten official knowledge. The Topographic Bureau of the Swiss Army was founded in 1834, with Guillaume Henri Dufour in charge of making a 1:100,000 scale map, the Dufour Map. The National Mapping Initiative began in the 1870s, producing the Siegfried Map and eventually leading to the integrated Swiss National Map and even today’s SwissTopo app. This is also where many names really solidified. Cartographers sought input from locals when naming places, in some cases immortalizing one name over others, or sometimes marking multiple down in parallel.

In Switzerland you can often look very closely at maps to see incredibly granular place names, including small meadows and fields, a particularly mountain ridge—things that where I come from in the Rocky Mountains, we have no name. However, when I began looking through the Apsáalooke Place Names Database (based on the Crow language), I was able to add alternative names in OpenStreetMap, such as where Elk Mountain in English was called Bull Mountain in crow, or Chíilpawaxaawe. Meanwhile, places with no name on the US Geological Survey maps had names in Crow, like Báachiihachke, meaning “long pine”, cited as:

“Ridge on old road from Garryowen to Lodge Grass, Reno District. (Benteen at Shavings Creek). An extraordinarily large pine grew on the ridge.”

In Switzerland, this level of detail exists, often due to the similar nature of the long term inhabitants (hundreds or thousands of years) who used these names for conversation and navigation. Of course, in the desolate parts of Western America, cowboys and trappers also had their own names, often still unmarked on maps, derived from native names or made up entirely on their own. So many of these are unmapped, and even where the name is known, perhaps the location is not.

One of my favorite regions on the entire planet consists of a particularly sunny, high altitude, and remote part of the Alps. I am not sure it has a particular comprehensive name as a region. In Switzerland it is the Upper Engadin (the valley where the river Inn, of Innsbruck fame originates). In Italy there is Val Venosta, but the majority of its residents speak German and might call it Vinschgau. Further to the east is the Alto Adige—the upper origins of the river Adige—which is also in German called Sudtirol, referring to the southern part of what otherwise forms a large part of modern Austria, Tirol. Of course, this region is an alpine paradise, and really is quite distant from civilization if you focus on the western half, from Merano to St. Moritz. However, my favorite thing about it is the linguistic mixture.

On road signs in this area, you commonly will see names in several languages. You will see the same on the cover of the Swiss passport—German, then French, then Italian, then Romansh. This latter language is fascinating because much of southeastern Switzerland features place names in Romansh, even where the residents speak German. In the Alto Adige, some villages speak Ladin, which is related to Romansh, and even further east in the Alps people speak Friulian, also related, just before arriving to the Slovenian border, where otherwise Italian language slips into a new Slavic tongue.

Back to my favorite area, you can see the cultural influences. It is not really a Swiss German place, in the way that Central or Northeastern Switzerland area, which starts to fade into German and Austrian culture, nor is it really Italian the way you may see around Como (the Insubria region), which borders it. Instead, you see this architectural style that has some nods to Tirol in Austria, but to me seems very Romansh. Towns have multiple names, like the famous St. Moritz being San Murezzan in Romansh, or San Maurizio in Italian. Hotels use the word “chesa” meaning house (casa, haus), and lake is “lej”. Various mountain peaks have a Romansh name, using “piz” meaning peak, retained even in the German names.

Much of this is a nod of respect to a threatened language and culture, and a signal of hope to save it. This may be the very same sentiment that has preserved local names in New Zealand or North America. Romansh has maybe 60,000 native speakers, and that number maybe doubles if including speakers with some level of proficiency. It could be gone in perhaps 4 more generations, up to 120 years—but will the place names remain?

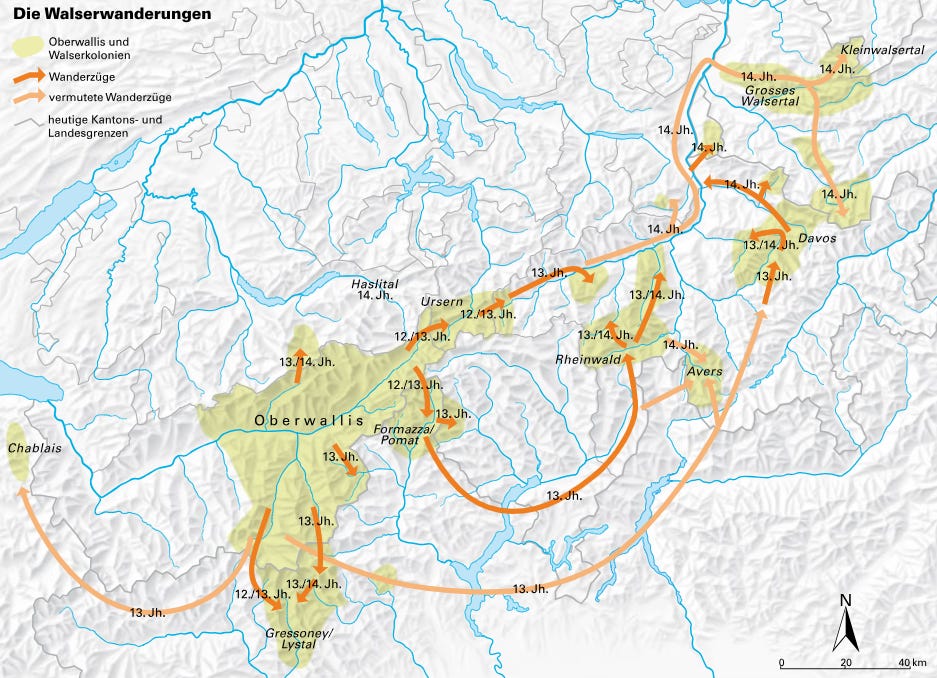

Much of this region was originally Romansh speaking—originally, meaning in the early Middle Ages. Romansh, Friulian, Ladin—these are Latin languages, related to Romance but not the same. They evolve directly from Vulgar Latin, the spoken language of the Roman Empire that would spread through the Alps. This replaced the preceding Celtic language, and often the people such as the Helvetii tribes. Centuries later, the Walser people moved in, migrating out of the area known today as Wallis (Valais in French), and with a very particular Alemannic German dialect.

Many iconic Swiss, Austrian, and Italian ski towns have a Walser history and appearance. Davos, for example, while in the heart of historic Romansh territory with the name itself coming perhaps from Romansh dava, or “meadow”, is a Walser colony. The names of existing places probably became a blend of Walser and Romansh, but by the late 20th Century both languages declined and Walser itself might be totally extinct as a native language. Both were alive long enough, however, to influence the names on maps, as well as to grant new names to newly settled areas, mostly for animal herding.

The Walser and Romansh story is perhaps the same in hundreds of other cultural regions around the world. Speakers of the dominant language in these regions today often see the places as just a name—not something incredibly descriptive, because they do not know its meaning. For English speakers, we can think of contrasting examples of this. We know San Francisco is the name of an Italian saint, but California has a more obscure origin (a fun read and memorable, but unknown to most). Greenland and Iceland seem perfectly descriptive, as well as White Sands, New Mexico or Salt Lake City, Utah. Others require some language skills, like Cardiff in Wales, using "Caer" (fort) and "Dyf" (the river) from Welsh, or Interlaken in Switzerland that is actually more Latin influence, meaning “between the lakes”.

On the micro level, where these types of names are applied to small locals like a specific beach or meadow, the real meaning seems to fade to locals over the centuries, because of language and dialect shifts like the Walser and Romansh areas saw. This is where we begin to wonder what our future maps will say—will the names of our common places change, and new names emerge? This is not just something like when Liberia and Sierra Leone entered the global map, or Czechoslavakia becoming two separate locations, or the Soviet Union disappearing. It is these small immediate places that we use in everyday speech that are the most subtle yet malleable.

Cities are full of these things, where neighborhoods or street corners gain a nickname. New York has several, like Hell’s Kitchen or SoHo. New generations of people can often mean new generations of names. One interesting manifestation of this is the website Hoodmaps, which gives users the ability to label neighborhoods with what sort of “vibe” they have, often on the pixel level of the raster map. This kind of crowdsourcing of information about different spots on the map, including text notes, reflects the way that people see places of course changes, but might also change how places are discussed and even named in the future.

Of course, urban areas are much more prone to this change, while rural areas may go a different direction: places names are more likely to fade and be forgotten, and the places become nameless. Without SwissTopo to tell me these small names of places I hike through, I would unlikely use them to tell others about my hike—telling them a good place to stop for a view or to turn left—and instead I would simply use something more anonymous. And what is more anonymous than a toponym? GPS.

Navigation is something that became very mathematical, robotic, and void of human culture. We know this in terms of road atlases, where people today follow where the screen or the voice tells them to go, rather than needing to unfold a large canvas to investigate the landscape and determine a route, to understand the connectivity and the relevant names as cues beforehand. Walking through a city, as well as hiking over a mountain, often looks mentally more like a chart or a graph, than being more verbal and descriptive. Even maps of landscapes in older times were more of a representative artwork (think of Lords of the Rings even), giving some emotional sense of a place and the words that name it, rather than an analytic model of reality with extremely literalism.

A revival came at some point, perhaps around the time that Google maps started to implement Live View, where the user is asked to point the camera of their mobile phone at the world around them to get oriented and see directional arrows. Google began to slip in small cues, more natural, like “turn left at the Costa Coffee”. While this is only a thinly veiled programmatic routing algorithm that queries nearby points, it got attention. With the birth of LLMs that can attempt to emulate human conversation, navigation, especially on foot, could start to feel more like being guided by a local than routed by a computer.

It could be especially relevant if computers begin to understand, visually, the real time environment. Being told to cross the street toward the red building, and look for the green door that is behind the yellow Toyota, the user really is on the same page as the navigation software. Understanding small colloquial place names can also be an advantage, although it is not easy to imagine this quickly—perhaps more for hiking than urban wandering.

As digital systems do more analysis and presentation of maps, the changes in names and meaning that you can see in the Alps also become a modern challenge. Postal systems (which I hope to write more on in another article) made incredible feats, especially in the early modern era, by creating or cataloging street names, house numbers, different buildings, level, suites and units, and essentially creating a positional label for every place able to receive mail, which also makes sense on a map (like sequential addresses on the same road, shared post codes).

Now like Romansh fading and standard German arriving, places have of course longitude and latitude, or Placekeys, or Google Plus Codes, or S2/H3 cells, or What3Words. There is tension and opposition. Places that did not have a navigable location now have one, while those that did as an address have some arguing for replacing to this new system. Could digitalization of location names erase the human element, where things have meaningful names, and make it all very mathematical?

I conclude this piece by not only reflecting on what may change, but also on what has already been lost. Think about the places around you—do you know their names? Do you know the meaning and the history? Do you have names for places, but which no map names? Are there forgotten names that you can recover and add to OpenStreetMap? All of these questions are a good exercise in spatial awareness, and hopefully we can all come to understand and map the toponymy, fading or emerging, of where we live.